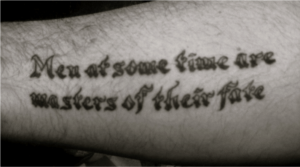

“Men at some time are masters of their fates.”

“Men at some time are masters of their fates.”

Cassius, to Brutus, Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene 2.

It’s almost axiomatic that we should sign up for goals only if we have control over achieving them. In Julius Caesar, Cassius berates Brutus for allowing himself to be treated as an underling; so to, conventional wisdom says that executives shouldn’t allow themselves be held responsible for the performance of other organizations.

It’s a nice theory. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work in the real world.

First, like it or not, Support can’t be measured separately from the rest of the company. Perceptions of Support are deeply enmeshed with perceptions about the product, its quality, and its supportability; by company policy; and by margin requirements levied by the CFO and Wall Street. Studies show that the single most significant factor determining Support customer satisfaction is product quality. No organization is an island, and least of all Support.

Secondly, what’s the point in optimizing the performance of Support—or any other organizational silo—if has the side effect of sub-optimizing the performance of the business as a whole? For example, Support can deliver great First Contact Resolution (FCR)…if they’re solving the same, well-known problems over and over again. This is great for Support’s numbers, but terrible for customers and the company.

Patrick Lencioni is a careful student of corporate culture. In his book Silos, Politics, and Turf Wars, he dramatizes a number of environments in which various organizations were at each others’ throats. While industries and details differed, the common theme was that each organization was working to meet its own objectives independent of those of other organizations. This put the various orgs at cross-purposes. Predictable conflict ensued.

This is old news to those of us who have been working in high tech for any length of time. Sales struggles to make their numbers, then blames product delays, feature deficiencies, and Marketing ineptitude. Product implementations go off the rails; Implementation Services blames Development, while Development wonders who hired these wet-behind-the-ears implementation teams. The Product Management team wonders why no one ever builds the impossible products it dreams up, and everyone knows what happens to Support. It’s a mess.

In this environment, does it really make sense for us to isolate ourselves from each other’s metrics? Because clearly, our successes can’t be independent from that of other organizations. As a CEO once told me early in my career, “David, there’s no way your department can succeed if the company fails.”

Lencioni proposes a two-part solution: a rallying cry (or overarching vision) for the whole organization, and cross-functional metrics to ensure that we’re all working together and supporting each other in executing on that vision.

This is a reason I love the Net Promoter Score (NPS), at least when it’s used right. (It isn’t always used right; we’ll have a Metrics Myth about that soon.) No one organization can own NPS, and everyone needs to work together to improve it. Unlike our siloed metrics of FCR, service level adherence, or customer satisfaction, something like Net Promoter Score gives Support a seat at the table. It gives a reason for Development to listen to us when we talk about customer experience improvements in the product, and it gives Marketing a reason to pay attention when we make the case for exposing known issues.

As with SMART metrics, keeping our heads down and focusing on Support metrics is more comfortable than living in a world where we’re dependent on others. But, since we can’t be successful without the rest of the enterprise, let’s pick cross-functional metrics that line us up in the same direction instead.